Home » Modules for Journalists » Showroom » Constructive approach » Essentials

Main topics: Constructive journalism introduction, change of mindset and focus, add-on to investigative and breaking news, three constructive pillars,elements of a solutions story, goals of constructive journalism,what constructive journalism is and what it is not.

Summary:

Constructive journalism is an approach that aims to provide audiences with a fair, accurate and contextualized picture of the world, without overemphasizing the negative and exclusively focusing on what is going wrong. It’s a response to the increasing tabloidization, sensationalism and negativity that dominates much of the news media today. It aims to introduce journalistic innovation to tackle some of today’s problems around news consumption and engagement. It is not a reinvention of journalism, rather it is a shift in focus and tone that includes solution, nuance and dialogue. Constructive journalism has the rigor and critical eye of good journalism and is modeled on three “pillars”: (1) solutions, (2) context and nuance, (3) dialogue and engagement.

Traditional journalism focuses on challenges and problems, thereby fulfilling an essential watchdog role. But it usually leaves it at that. That’s because journalism’s predominant theory of change says that simply uncovering problems leads to reform. However, proponents of constructive journalism take a different approach; they say that this theory of change is incomplete, insufficient and not enough to resolve problems. Why? Often a community lacks awareness or the knowledge about how to successfully meet challenges it faces. Or people don’t have the tools and methods needed to engage in meaningful dialogue. Or community members might not have sufficient information and context to fully understand the complexity of an issue.

A constructive approach to journalism takes a different look at the media’s role in society and how media practitioners approach their work. It asks the media to consider if the old model is working or if it is time for something new?

The concepts behind constructive journalism have been explored, discussed, reviewed and explained by scholars, researchers and practitioners for around two decades. There’s no one definition they’ve all agreed on.

The Constructive Institute (CI), based at Aarhus University in Denmark, has been one of the main drivers in conceptualizing and organizing the constructive journalism approach. The institute defines constructive journalism as “an approach that aims to provide audiences with a fair, accurate and contextualized picture of the world, without overemphasizing the negative and what is going wrong.”

That is, instead of only about what is broken, the journalist working in a constructive mode also reports about things that work. Constructive reporters move beyond being a notice board for the public’s problems and fears. They see their role as a more active one in serving their community and society as it seeks solutions and ways out of division.

In addition, constructive journalism goes a step further than problem-centered journalism and asks: now what? Its philosophy is: We know what the problem is, but let’s also talk about what people are doing about it and how to move forward. This is in contrast to much journalism, which is firmly oriented toward the past. While this usual look backwards does make sense as journalists usually report on past events, adding an orientation towards the future can transform conflicts into possibilities. It allows journalism to explore opportunities for progress instead of simply rehashing a problem once again.

Below is a more detailed explanation of some of the main principles and ideas characteristic of constructive journalism.

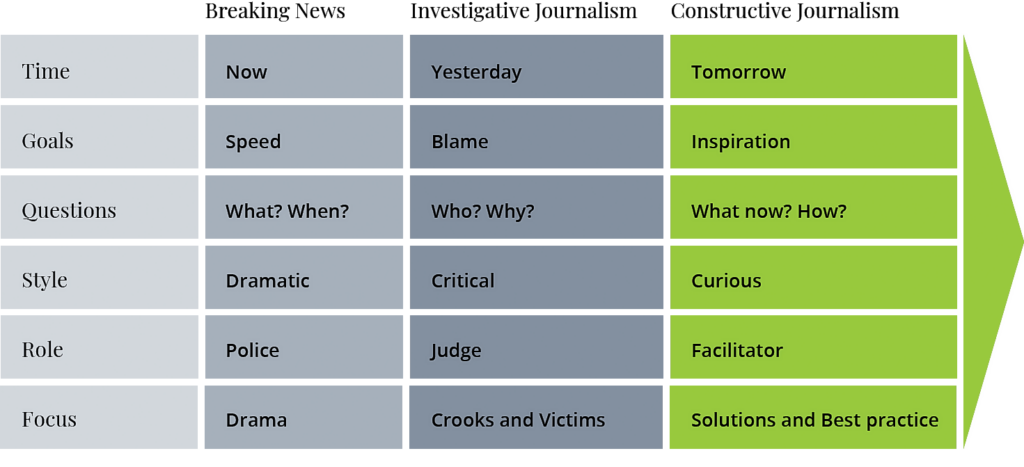

An additional layer: The Constructive Institute sees constructive journalism as a new take on traditional reporting, an add-on to the journalist’s toolkit, not a wholesale reinvention. Constructive journalism can easily complement breaking and investigative news.

Some characteristics of three types of journalism (Source: Constructive Institute)

Shift of mindset: Constructive journalism shifts away from focusing solely on conflict and negativity. It seeks to break ingrained habits that have become reflexes for many journalists, such as:

Framing: This refers to how issues are packaged and presented to consumers of news. In a news story, a frame is “a central organizing idea or story line that provides meaning to an unfolding strip of events weaving a connection among them. The frame suggests what the controversy is about, the essence of the issue.” It’s the process by which journalists select aspects of a story and highlight or downplay them in their reports. Framing strongly affects how a news event is perceived by the audience and is influenced by things such as the choice of words or images, or which facts reporters include. Problem-based journalism often chooses a negative frame, highlighting what is bleak. Constructive journalism seeks to shift the frame away from total doom and gloom and towards another perspective, such as a solution, resilience or cooperation.

Positive psychology: Constructive journalism draws on the field of positive psychology, which is a scientific approach to studying human thoughts, feelings and behavior. Positive psychology puts the focus on strengths instead of weaknesses instead of focusing on mental illness and negative thinking. Some constructive thinkers like the Danish journalist Cathrine Gyldensted recommend applying positive psychology’s PERMA model to constructive reporting. The acronym PERMA stands for Positive emotion, Engagement, good Relationships, Meaning and Achievement. According to the founder of the positive psychology movement, American psychologist Martin Seligman, these are key elements for a flourishing life which enable people to overcome “learned helplessness”, which can be a byproduct of exposure to too much negative news.

Return to core journalistic values: In many ways, constructive journalism takes reporting back to the core values of balance, fairness and sober-mindedness – values that have often been lost among all the noise and the race against time. Reporters taking a constructive approach still need to conduct thorough research, investigate claims and get different sides of a story. But additionally, they need to explore solutions being tried, go deeper and leave their biases at the door.

Adjusting newsroom practices: The shift away from problem-centered journalism toward this forward-looking approach impacts every step in the newsroom workflow.

![]() See Handout 2: Constructive Journalism – institutions, dedicated media outlets and formats

See Handout 2: Constructive Journalism – institutions, dedicated media outlets and formats

Constructive journalism serves as a catalyst to enable dialogue and participation through open, engaging, solutions-oriented and comprehensive media reportage. The model aims to breathe new life into journalism by encouraging open conversation and enhancing grassroots participation in communities, things on which healthy societies depend.

Element 1: Solutions

Often, news consumers only get stories about failure. Failure of people, failure of institutions, failure of governments and societies. This begins to erode trust. Constructive journalists report on problems, of course, but they also look at solutions to these problems that are being tried out. There are things that are going right in the world after all, so let’s also talk about those. People don’t change merely because someone points out their problems. They need to know that change is possible and see models of how to do it. Societies work the same way.

For example, what initiatives, projects, innovative approaches and programs have been implemented to reduce poverty, decrease polarization, increase literacy and enhance access to quality healthcare and education? Constructive journalists seek out approaches by groups, governments and individuals and explore if they’ve worked, if they’re sustainable and whether or not they could be replicated in other places where similar problems exist. A solution in one region might work in another, or it might not.

Using the word “solution” can imply that the journalist is claiming that something will completely resolve a problem. This isn’t the case – or at least not very often. The bigger a problem, the more complex it is and the less likely it is to find a perfect solution that works for all. The New York-based Solutions Journalism Network, a major advocate of a constructive approach, prefers the term “response”, which makes sense. Journalists should be clear-eyed about a response’s success rate and then report accordingly. Some responses are successful, others less so. The goal of a solutions story is to yield practical insights about how a problem could be addressed. Even responses that have not been successful can provide valuable lessons.

Example: In Bangladesh, more than 1,500 people drowned in less than two years, more than 70% of them children. The traditional story relates those statistics and leaves it there. The constructive one notes that child drowning is a serious problem, but then highlights a program by a non-profit group that teaches children in villages how to swim. In the program’s three years, the number of drownings among children between five and nine dropped 48%. It’s an approach that might be replicated in other areas with a similar problem.

When can you use the solutions approach? Most responses to problems can be good candidates for solution stories. This approach is probably not suitable for fast-moving, breaking news, but it can be right for second-day or longer-term follow-up stories, providing a fresh follow-up angle to news events.

Ingredients of a solutions story: Some solutions stories come in for criticism as simply pointing out something done by a “do-gooder”. This kind of story is advocacy or promotion, the critics say, which is not good journalism. In response to that, the Solutions Journalism Network has identified four criteria that a solutions-centered story should contain in order to meet its standards of rigorous journalism.

Element 2: Nuance and perspectives

Constructive journalism approaches embrace complexity and context in order to provide a more accurate view of reality and a deeper understanding of issues. It explores shades of gray rather than black-and-white versions of the world. Instead of boxing complex issues into fiery soundbites and punchy “gotcha” quotes, constructive journalists provide context to complex issues such as the local impact of climate change and corruption. They explore various perspectives and avoid stereotypes and clichés, as well as overly emotional, sensationalist or polarizing language, even in the immediate aftermath of crisis or tragedy. They challenge accepted beliefs and even their own hypotheses about stories or issues. If the reporting leads the journalist to abandon an idea of what a story is about and show a more complex reality, that’s fine. It’s about being honest and truthful, about seeing the world as it really is – taking in the full view and not a preconceived one.

Examples: The traditional framing of Africa can swing between extremes. The often-cited Economist front covers about Africa illustrate this “black or white” approach. A cover from the year 2000 labeled Africa a “hopeless continent” while one from 2013 declared that Africa was “rising”, depicting the entire continent as a rainbow-colored balloon soaring into the sky. Without nuance, the problem of bribery and corruption in Africa is often projected as an inevitable product of greed of politicians and business elites. A nuanced analysis could show the structural failings of government systems, offer historical background and comparisons to other regions. This may start a conversation on ways to move forward beyond the paralyzed acceptance of the current reality.

When do you include nuance and perspectives? Pretty much any story. Covering nuance and complexity is simply good journalism. Of course, how much depth a journalism goes into depends on time, resources and story length. But even short stories can adapt constructive elements. More on this in Module 2, Chapter 1.

Element 3: Constructive dialogue

Constructive journalism encourages calm and curious conversation about the issues that concern communities. This includes using audience input to identify stories and engaging the public as a story is being reported. It also aims to facilitate constructive debates, even across yawning, difficult divides. The journalist acts as a facilitator of discussion and debate. With an open mind and a careful language, a journalist can explore political topics constructively without inviting accusations of bias from political actors, especially in a polarized democracy. The facilitative role also requires journalists to boost “alternative discourses that are affirmative, creative, under-reported and give voice to underrepresented social actors”. The larger public, not just the elites, are at the center of the news and the conversation around it. the journalist acts in the public’s interest.

Example: The German weekly newspaper Die Zeit ran a series called “Germany Talks”, bringing people from different backgrounds and different opinions on topics together to talk. Their paths otherwise would probably never cross. They sat down together and sometimes found common ground, sometimes didn’t. But even if their opinions didn’t change much, they usually did end up seeing each other as people with legitimate views, not just adversaries. For example, the project brought together a rural man who likens urban environmentalists to terrorists with a city resident who wants more wind turbines.

When can dialogue help move things forward? Opportunities for fruitful exchange and constructive debate will arise with issues that concern the public, are relatively well known and have already been part of the public conversation.

![]() See Handout 3: Constructive story examples from around the world

See Handout 3: Constructive story examples from around the world

Do we learn more about motivations and experiences behind opinions?

Constructive journalism seeks to make the news environment less toxic by acting as a countervailing force to all the noise and negativity. Its overarching goals are:

Constructive journalism doesn’t seek to avoid bad news but rather provide balance. It says journalism should cover the bad while not forgetting the good – stories of inspiration, resilience and innovation belong in the news as much as car accidents, riots, violence and tragedy. Instead of contributing to a sense of despair, the constructive approach aims to inspire and motivate the public.

In an era of increasing divisions in society and decreasing trust in the news, a constructive approach can lower the overall temperature by presenting fact-based, researched stories without resorting to sensationalism and the shouting of highly opinionated firebrands. It wants the news media to seem less overwhelming. In the age of the 24-hour information torrent, the constructive approach slows things down a little. It seeks to give people room to think while giving them the whole story.

Constructive Journalism is:

Constructive Journalism is NOT:

“Western” principles of journalism have over decades dominated journalism education in the Global South – principles that were deeply rooted in traditions and political realities of Europe and North America. The concepts of constructive journalism are one response to the global crisis of media in the digital age, but have mainly been developed, again, in Europe and the United States. Can they nevertheless be relevant for media professionals in other parts of the world?

Some similarities: Both digital disruption and journalism cultures that follow the “if it bleeds, it leads” principle are found in newsrooms across the Global South. However, there are a range of realities in these regions that will impact the possibilities and potential of constructive journalism as well as its implementation in the local context. Some are below.

Societies in conflict: In a context of violence and high tension, journalists must take great care when considering the language and framing they use. These choices can exacerbate volatile situations. In such cases, constructive journalism approaches should be combined with elements of conflict-sensitive reporting.

Examples: The Danish media development organization International Media Support and the Constructive Institute carried out two constructive journalism projects. The first one, located in Colombia, looked at the protracted war there and how it was reported. It also considered a recently signed peace agreement and the need for journalists to engage in democratic conversation about the country’s future. A guidebook was also published (in Spanish). The second project was a curriculum developed with the American University in Beirut which taught both constructive and conflict-sensitive journalism in one class of Lebanese journalism students.

Levels of democracy: The stated ambition of the constructive journalism model is that its reporting will contribute to and support democracy. In authoritarian regimes, there is a high risk that constructive journalism could be misused and many urge reporters to use caution. According to some experts, there is often a problematic demand for “positive”, uncritical news about governments. Constructive journalism should be separated clearly from notions of uncritical journalism. Instead of increasing trust, a constructive approach here might do the opposite as it could be perceived as “airbrushed” news, biased and even propagandistic. The promotion of dialogue and engagement, pillar three, could be difficult or dangerous under authoritarian regimes. But even in an authoritarian environment, a constructive approach on the local level with local issues that are not politically sensitive might well be possible.

In young and relatively stable democracies in the Global South, media experts see opportunities for journalists to work constructively and act as the fourth pillar of democracy. According to journalist Cathrine Gyldensted, constructive journalism is “holding power to account by asking them to solve, collaborate, seek a civil debate – instead of usual conflicts, disagreeing, polarization”. Some media professionals are concerned that when people are encouraged to fix their problems on their own, government officials might be tempted to lean back and stop making any effort at all.

Constructive = complacent? In an interview with the World Editors Forum 2014, Prof. Anton Harber from WITS University South Africa expressed his fear that journalists would try to be positive at the expense of truth telling. “News is only constructive if you want a sleepy, complacent society, not if you want active, engaged citizens.” According to Harber, constructive journalism undercuts the journalist’s central role of calling the powerful to account. However, constructive journalism proponents counter that ethics and standards, good reporting skills and a critical eye are all key elements of their approach.

Post-colonial heritage: Sanne Rotmeijer analyzed local journalism on the Caribbean island of St. Maarten and found a culture in which people live in small communities, are related to many others in those communities and fear outspokenness – a reflection of the colonial past. Constructive stories about local businesses that seek to foster economic development could easily become PR. To her it seems counterproductive that local journalists use words of inclusion in news stories, while the same local journalists do not have the capacity or the courage to address ongoing policies of exclusion. Under such circumstances, and they might be similar in other post-colonial societies, a journalistic focus on social stability would reproduce “the local ‘sugar coated’ community and may play into the hands of the ones in power”.

Building bridges: Many societies in Africa and the Middle East are highly polarized. This makes it extremely difficult for journalists to avoid being used by one side or the other. Often, they are led into a toxic cycle of accusation and name calling by political and business elites. But when the media objectively reports on problems and solutions and offers nuanced coverage that acknowledges both sides’ viewpoints, officials and leaders can no longer argue that the media has an agenda since it reports on wrongdoings and on solutions regardless of who is behind them. Journalists can also build bridges between communities and guide democratic discussion into areas which directly impact audiences, such as education and climate change.

Initiatives in the regions:

The Middle East: Young journalists and small media startups are starting to get interested in the constructive approach even though there are hardly any best-practice examples of constructive journalism to be found in Arabic. In 2020, former BBC journalist Dina Aboughazala launched Egab, a solutions journalism initiative for local journalists in the Middle East and Africa. The aim is to help journalists in these regions successfully pitch to international news outlets. Egyptian by birth, Aboughazala wants to shift how her region and others are perceived both at home and abroad. Egab’s name is derived from the Arabic word Egabiya (positivity) and Egaba (answer). “Egypt is always in the news for the worst reasons. People think that countries in my region – the Middle East & Africa – only offer problems and there’s no chance anything will be fixed” she said.

Africa: Even though constructive journalism is still not very widespread in African countries, more and more young media outlets or platforms like Africa No Filter (bird stories) have started to tell African stories differently. They have stopped copying the perspective of international media from the Global North and begun countering stereotypes and providing inspiring and solutions-focused stories. Same for African Arguments, a pan-African platform for news, investigation and opinion that seeks a diversity of voices. The Kenya-based Mobile Journalism Africa network of journalists takes a similar approach while shrinking the gap between reporters and sources with mobile devices. Many experts complain about a lack of professionalism and a lack of transparency regarding media ownership. But over the last years, media initiatives in many African countries have set up fact-checking and verification platforms and trained other media professionals. First steps in constructive journalism could build upon these initiatives and the journalists they have trained. After some best practices are in place and a few success stories publicized, more media managers and editors could become interested in the approach.

South Asia: Media practitioners and analysts in South Asia see the benefits of constructive journalism in their region similarly as proponents in Europe and North America do: countering a conflict-only narrative that has taken hold in the media and giving room to stories of solutions and even inspiration. There is already some engagement with the constructive approach in South Asia, particularly in India. Two online operations there, The Better India and The Quint, regularly do constructive stories, although the former sometimes veers into positive journalism.

Given the stretched resources of most South Asian news operations and the traditional attitudes shared by many experienced journalists, small experimental steps at the beginning will be important as well as convincing media house owners and editors of the value of this new approach. One risk is that constructive stories could be perceived as PR. If news coverage puts the government or military in a good light, observers from Pakistan pointed out, there would be suspicions that the news organization was trying to curry favor with those in power. Local issues and local media are the most promising testing grounds for a constructive approach, and young people are likely to be more open to it in general. They are underserved by the media and rarely see their concerns addressed.

![]()

What is Constructive Journalism/CoJo? (Caterine Gyldensted’s website)

www.cathrinegyldensted.com/constructive-journalism

What is Positive Psychology and How Can It Help?

www.talkspace.com/positive-psychology-definition

Innovating News Journalism through Positive Psychology (2011)

www.repository.upenn.edu

Solutions Journalism Toolbox, Solutions Journalism Network

www.learninglab.solutionsjournalism.org/basic-toolkit

Discovering Solutions: How are Journalists Applying Solutions Journalism to Change the Way News is Reported and What Do They Hope to Accomplish?

www.digital.library.unt.edu

Interview with Die Zeit-Editor in chief Maria Exner on “Germany Talks”:

www.youtube.com/Maria-Exner

‘The audience wanted this’ – moving past problem reporting and focusing on solutions

www.thewholestory.solutionsjournalism.org

Explainer: What is Constructive Journalism (Constructive Institute)

www.youtube.com/explainer-constructive-journalism

Solutions Story Tracker, Solutions Journalism Network

www.solutionsjournalism.org/storytracker