Home » Modules for decision-makers » Factory Floor » Reporting constructively » Essentials

Main topics:

Topics suitable for a constructive approach, thinking creatively, covering a story constructively, working with data, desk and field research, constructive interviewing, the hero’s journey, constructive at every stage of a story.

Summary:

Constructive reporting has all the elements of good, traditional reporting. But journalists working in a constructive mode add context to their stories and ask future-oriented questions – the “What Now?” element. Many kinds of stories can be approached in a constructive way, although fast-breaking news might not be suited to such things as a solutions approach. The constructive approach asks journalists to look at problems in a new way, which calls for creativity and unconventional thinking. Constructive journalists put an emphasis on looking for fresh perspectives, being empathetic when interviewing sources and letting go of assumptions. Constructive techniques can be integrated into every stage of the story production process.

Journalists who produce constructive stories say that the approach is suitable for a wide variety of topics: Health, the environment, climate change, human rights, social justice, education, technology, integration, etc. Wherever there are problems, journalists can look for people or organizations working on responses and report on them. Constructive journalism also has the potential to get polarized communities talking about divisive issues, and perhaps finding some common ground. This is especially the case during tense moments such as elections. However, promoting constructive dialogue on some topics might be difficult or impossible in countries where freedom of expression is low or not existing.

So, while many stories can have constructive elements in them, some formats and topics may be better suited to certain of the “pillars” – solutions, context and nuance, dialogue and engagement – than others.

Breaking news: The solutions approach might not be suitable for breaking news, where getting the facts out fast is the priority. It can be right for second-day or longer-term follow-up stories since solutions stories can provide a fresh follow-up angle to news events. Solutions stories are often more suited to a cooler stage of a topic’s life cycle. Similarly, some aspects of the dialogue and engagement pillar can be difficult to apply when a story is breaking. Constructive dialogue usually comes later.

However, a constructive approach that adds context and complexity can be used even with brief reports and fast-moving news. The Danish news agency Ritzau encourages reporters to ask a few extra questions by doing the following:

Tragic events: Some journalists admit that there are highly emotional topics like death and tragic accidents “where compulsively looking for a constructive perspective is simply inappropriate”, at least in the very first reports following the event. In news agencies and newsrooms in particular, where journalists work under time pressure, the potential for a constructive approach might be limited. However, sometimes a more careful choice of images and wording, one that doesn’t inflame tension or cause great fear, can be a positive step in the constructive direction.

Silver-lining stories: In cases of disaster and turmoil – whether natural or man-made – journalists might look for “silver-lining” stories of not only survival but success, brilliance, solidarity, and extraordinary achievements. This doesn’t mean downplaying tragedy, but to look for some positive element or development that comes in its wake.

Example: In the aftermath of a bomb explosion, breaking news offers crucial timely information but is not necessarily constructive. Investigative journalism serves a watchdog role which will ascertain who is to blame for the bomb and the lapse in security. A constructive journalism approach could explore efforts to prevent this kind of violence from occurring again – the “how do we move forward?” aspect. |

Constructive journalists aim to move beyond the mindset that conflict-based, negative stories are the newsworthy ones. To do that, they need to look beyond traditional news values, and consider adding others to that list. Besides “good news”, these additional values could be “solution”, “cooperation”, “visual”, “emotions”, “relevance”, “follow-up”, sometimes even “surprise” – without falling into the trap of sensationalism. Researcher Perry Parks from the University of Michigan (US) has even advocated for “joy” as a news value. The constructive approach often challenges journalists to seek new ways of looking at problems. How can they become more creative and think outside the box?

![]() See handout 1: Re-examining News Values

See handout 1: Re-examining News Values

Undergoing filters: Our brain is a self-organizing system. What we have experienced in the past influences the direction we take and makes us feel safe. Among other filters, our mind uses a “feasibility filter” that often hinders open-minded reflection (this takes too much time; costs too much money; this can’t work, etc.). “Negativity bias” also influences the way we react to new ideas. To loosen the tight control that our rational-logical (linear) thinking normally has on our mind we need irritation.

Some techniques to become more creative:

The creative process needs chaos, not control. Only when we have gone through this phase should we move on to the second one: structuring ideas, clustering and prioritizing them according to relevance and usefulness for the target group or to the potential for solution finding.

![]() See handouts 8 and 9: What type of creative person are you? Explore your creative potential!

See handouts 8 and 9: What type of creative person are you? Explore your creative potential!

The PERMA model: Most journalists tend to think along the same lines and thus have similar ideas for story angles. The world keeps being portrayed in a certain way – everything that’s wrong with systems, institutions, politicians, etc. But according to constructive journalism proponents such as Cathrine Gyldensted, this violates the journalist’s ethical guideline of seeking truth and reporting it, since it’s not the whole truth. She and others suggest trying another framework for brainstorming story angles and ideas – the PERMA model, which is based on the positive psychology work of Martin Seligman in the United States (also see Module 1, Chapter 2). When looking for stories and angles, journalists working constructively can consider the model’s five elements of well-being and add questions to them:

Examples: After a natural disaster, the media could report on how people are helping each other, inviting neighbors who have lost their homes or their power to stay with them, strengthening the social fabric. The media could talk to rescue workers and describe how they find meaning in helping people. |

The PERMA model elements also offer a framework for reporters to identify positive threads within the top news stories that are already there to produce follow-up pieces.

Engaging the audience/community: Journalists can identify problems by listening to a community. To report constructively, it’s crucial to know as much as possible about the audiences and the problems they face. In reaching out to the public, reporters learn what’s important to their communities, access information and get in contact with sources. Media outlets and newsrooms have various options to interact with their audiences and build a community, such as social media channels, comment sections and public events (see Module 2, Chapter 3). But freelance journalists and photographers can also find ways to engage audiences. They should get into the routine of asking friends, acquaintances or interviewees if they’ve heard about an interesting approach to a problem or even some positive development around an issue. If they have a following on social media, they can put questions to their followers.

Finding stories in data/positive deviants: Journalists may also find solution story ideas in data, since it can show how a response has been working and give measurable evidence. Usually when searching data, journalists look for the worst cases. For constructive reporting it can be interesting to look at the data differently. For constructive reporting it might be interesting to look who is doing the best? Another option is to look in the middle. What does the data say about the majority rather than the worst or best case?

Another option is to look for “positive deviants”. These are outliers, responses that are bucking a trend. This is a way to work backward from evidence and find people who are meeting a challenge better than others. Deviation from a norm, but in a positive direction. In other words, who’s doing better than the others with the same resources? This is a signal that something newsworthy could be happening. It’s the journalist’s job to get the story behind the positive deviant and uncover information that could be valuable. Some journalists hesitate to attempt solutions stories because they don’t want to be labeled advocates or PR reps. But the data gives you evidence and shields you from accusations of advocacy.

Example: A dataset showing Covid infection rates in 2020 had many counties showing striking similarities. The curves on graphs representing infection numbers in Portugal, Italy and Hungary were almost identical. But the graph related to Kazakhstan had a completely different shape. Where infections in other countries were skyrocketing, in Kazakhstan they were falling. It was a positive deviant. The reporter then can take this information, do some reporting and find out what the country did to put their infection rates on a different trajectory. Perhaps Kazakhstan’s more successful response could be replicated elsewhere. |

![]() See handout 10: Using Data Constructively

See handout 10: Using Data Constructively

Looking at big problems? Large problems that are usually considered the responsibility of governments or even global problems can be addressed by investigating how individuals or local communities are dealing with them.

Example: Australia’s ABC News ran a story about an increasingly expensive housing market, one which has become unaffordable for many. The story looked at how some builders were reducing costs by designing houses on their own, taking over the unskilled labor themselves, using less expensive and recycled construction materials or sharing costs with other people. Affordable housing is a big issue that will not easily be solved by one program or government, but a constructive reporter can still address it by examining how individuals or communities are taking an innovative approach and solving at that level. |

Identifying potential pitfalls: Promising solutions can be found in many places and on many levels. But it’s important to not take a response at face value. Reporters have to do their jobs and look at possible negative sides of what might at first seem like a real success story.

Journalists should always remain curious, but critical about a solution. And they should never advocate for a specific one. The evidence of the response’s results and limitations should speak for themselves.

Sources for solutions stories: Journalists can go to a variety of individuals or organizations to find interesting responses to problems.

Example: Eromo Egbejule, West Africa editor of The Africa Report, participated in the Good Growth Journalism Initiative organized by UNDP in Peru in 2019. “I heard Costa Rica’s remarkable story. The country managed to reverse what was one of the highest deforestation rates in the world, with radical reforms backed by political willpower. It’s a lesson countries in Africa ought to learn.” Eromo detailed his findings in an article he published in the Africa Report: Lessons on political willpower from Costa Rica and Peru. |

Once journalists have solid ideas, they can sit down to do background research and decide how they’ll approach their topic and who they want to talk to. The PERMA method works here to help journalists identify positive threads in a story. (See the questions in the PERMA section above.) As constructive journalists plan and research, they keep their minds open, stay off of a predetermined path and let go of their assumptions. They let the story go where it will. Other aspects to consider:

Data mining and analysis: In case the problem is already known (such as climate change or water scarcity), or the journalist has identified a problem (such as people losing their jobs due to COVID-19), data mining and analysis can give a clearer idea about the size and impact of a problem.

Often, journalists can fairly easily pinpoint a problem through data, but it can be more challenging to find potential solutions. Sometimes, data can help or point in the direction of people who might be familiar with solutions being tried out. And of course, data sets often help to evaluate the success of a solution.

Finding information: In many parts of the developing world, hard data can be hard to come by. Nevertheless, there are ways for journalists to find information:

Fact-checking is crucial: Because constructive journalism often covers underreported problems or perspectives, constructive reporters often look for different, new or lesser-known sources. This makes good fact-checking and the vetting of sources all the more important. Verification and confirmation are key. Journalists should not jump to conclusions after just a first look at the results.

Using data constructively: Zoom into key data and zoom out to provide context

Steps to take:

Source: Minna Skau, Danish news agency Ritzau |

Looking for context and nuance: Constructive journalists examine the development of an issue over time by analyzing data, looking at the historical background and trying to get more than one perspective. While it’s easiest to go to one or two sources for a story, to get a more nuanced view, additional sources can fill in the picture.

On the ground research and the human face of an issue: While desk research is important, journalists should always get out of the office, if possible, and go out to where the story is. Data can tell you the size and impact of an issue in numbers and other statistics, but it’s by going out and talking to people that journalists learn how an issue or problem is affecting communities and individuals. This means paying close attention to their stories and listening to how they are trying to make sense of the problem. Who feels the need for change? Where? When? and Why?

To summarize:

Look critically at the response: Try to poke holes into any solution by talking to experts, opponents, considering counter-intuitive data, etc. to make sure it holds up to scrutiny. Is it really doing what its advocates claim? If it falls short, journalists should think about whether the story is worth covering. It may well be, because simply because a response is not perfect doesn’t mean it isn’t worthwhile on some level. Reporting on failure can be illuminating. But all problems or limitations should be covered. This is a central aspect of good solutions reporting.

Self-assessment: Authors of constructive stories need to ask themselves:

Constructive stories demand different interview techniques than those that have been taught over decades in journalism education. Questions should relate to the experiences of the interviewee regarding the story topic but they also try to uncover underlying motivations and feelings. Some of these techniques come from the dispute resolution process known as mediation. Mediators seek to deal with divisive issues by calming minds, opening up communication and finding ways out of conflict. Media professionals who conduct interviews like this say: it takes effort but it’s worth it.

Active Listening: Good listening skills are essential for reporters. They are looking for context and the underlying reasons for people’s stances and beliefs. They shouldn’t just listen for soundbites or the most extreme, shocking thing that’s said. The reporter should try to understand why people feel the way they do. What in their lives brought them to this place? It’s not easy. Studies show that most people remember less than 50% of what they hear in a conversation. To add to that, interviewers are already having to think about many other things during an interview (recording levels, camera position, background, time pressure, etc.). But the more reporters really listen, the more they’ll build trust, get their interviewee to lower defenses and get to the truth of the matter.

A way to achieve this is through active listening. In this approach, the journalist focuses on both the elements of speech and the interviewee’s expressions, and also on the intent and implications of the words. Active listening is focused and intentional and requires effort.

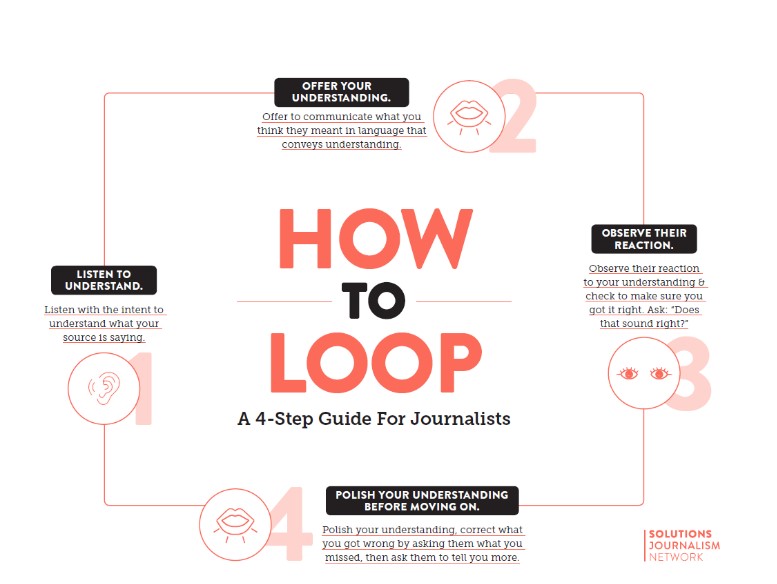

Looping: This technique – listening to understand – is a tool that mediators use to arrive at a deeper understanding of what’s important to people and why. Looping creates empathy because “empathic listening allows the speaker to think more clearly and more deeply,” according to the Urban Consulate, a US group which aims to make people talk to create more equitable communities. “When people feel understood, things go deeper.”

Looping is a technique developed by The Center for Understanding in Conflict and involves asking for confirmation to see if a listener has understood a speaker’s message correctly. The interviewer paraphrases statements in a neutral way that have been made by an interviewee to demonstrate he or she has fully understood the answer. This technique also tends to calm strong feelings if the topic is highly emotional or controversial.

Four-step guide for constructive interviewing: The Solutions Journalism Network has adopted this looping technique and developed the following four-step guide.

Source: Solutions Journalism Network

Example: Journalist paraphrases: You are worried about your safety and economic future if people come into the country who are violent or who get jobs. Is that right? |

Constructive questions: Constructive journalists ask questions that, even in a negative situation, explore different aspects of a story. They ask about resilience, about people who’ve helped, about a path toward improvement and for points of view that provide meaning. Constructive interviewing illuminates areas often left in the dark. And reporters should always keep in mind: ask questions about the future. Where do we go from here? What next?

Constructive journalism on a deadline: Busy journalists might feel they don’t have the time or resources to make a story “fully constructive”. And sometimes they’re right. To fully report a solutions story might well take more time and effort than a more traditional one would. But they would be surprised that even when working on a deadline, a few extra questions and looking ahead can work wonders.

Constructive stories should be particularly well told to attract the audiences and create impact. But what makes a story compelling? Are usual storytelling formats sufficient?

The hero’s journey: In the 21st century, the mass media and the film industry have mainly relied on the “hero’s journey” described by Joseph Campbell to tell compelling stories. A professor specializing in comparative mythology, Campbell described this journey in his 1949 book “The Hero with a Thousand Faces”. He found variations on a classical story structure in tales and myths from many cultures: The hero leaves for the quest, learns from a mentor, fights enemies, almost dies, resurrects, finds his power and returns with an elixir. This archetype of human storytelling fits to some extent quite well to the problem-solution shift in constructive journalism. But to make constructive stories compelling and inspiring, the main elements need to be slightly modified or adapted:

Choice of story elements: The “hero’s journey” story structure can be helpful to identify and choose the main story elements.

The main character: The choice of a main character is crucial for a constructive story: What can he or she offer? Share experiences, offer a solution or an idea that could encourage solution finding? Inspire? Is the person authentic to the setting? Affected by the context? Able to reflect the problem or show the bigger picture? Who is the best person to tell the story? Sometimes someone behind the scenes is more appealing than those in obvious positions.

Address the human face of the problem: Choose a relatable character. Give an example of a community member that is affected by the problem e.g., Urban females aged 12 -17 = a group of teenage girls, who live in Beirut.

Identify a relevant context/create a believable persona: Dig deeper into your data to identify other social or economic factors surrounding the people affected by the problem. Find a specific case or character from the community or build your own persona, e.g., urban females aged 12 -17 from low-income and poorly educated families = Sara, a young orphan teenager, who lives in slums just outside Beirut with her two little brothers. Developing personas might help to identify protagonists but also to better understand who the audience is.

Adopting a constructive mindset means thinking about constructive techniques from the earliest stages of the story process and applying them wherever is possible. At every step – from story idea to final product and feedback – journalists can work in a constructive mode. Here’s a recap:

![]() See handout 12: Being constructive at every stage of the story process

See handout 12: Being constructive at every stage of the story process

![]()

Finding a Solutions-Oriented Story: Introduction

www.learninglab.solutionsjournalism.org/introduction

Solutions Story tracker (SJN)

www.storytracker.solutionsjournalism.org

Fanning the Flames: Reporting on Terror in a Networked World, Tow Center, CSJ:

www.cjr.org/coverage-terrorism-social-media

Innovating News Journalism through Positive Psychology (2011)

www.repository.upenn.edu

Discovering Solutions:

How are Journalists Applying Solutions Journalism to Change the Way News is Reported and What Do They Hope to Accomplish?

www.digital.library.unt.edu

Active Listening Skills, Examples and Exercises:

www.virtualspeech.com/active-listening-skills

Positive psychology could revolutionise journalism

www.positive.news/positive-psychology-revolutionise-journalism

Leonie Gubela, Definition, Implementation and Effects of Constructive Journalism in German Print and Online Media, 2018

www.domedia.fra1.cdn/MA_Gubela.pdf

Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Penguin Books, 2012 (book)

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, New World Library, 2008 (book)

Matthew Winkler, Kirill Yeretzky, The Hero’s Journey according to Joseph Campbell, 2016

www.youtube.com/heros-journey

Africa no Filter, How to write about Africa in 8 steps

www.africanofilter.org/How-to-tell-an-african-story.pdf