Home » Modules for decision-makers » Marketplace » Moving your media outlet forward » Essentials

Main topics:

Editors/managers and support for constructive journalism, coverage priorities, implementing constructive journalism in the newsroom, impact studies, collaborative projects, metrics and analytics.

Summary:

If a newsroom or journalists want to introduce a constructive journalism approach or small-scale project, it’s essential to get editors and other newsroom decision-makers behind the idea. There is no single approach to integrating constructive reporting in newsrooms, it depends on resources, staff levels and priorities. Outlets interested in the approach don’t have to radically change the way they operate – a slow introduction is possible to test the waters. Impact studies on the impact of constructive stories on audiences as well as revenue streams look promising and media outlets would be well advised to use analytics to track the performance of constructive stories.

To successfully introduce constructive journalism at a media outlet and make it part of the newsroom culture, the people setting editorial policy have to be convinced of its benefits. Experience has shown that journalists introduced to the concept of constructive journalism, for example at a workshop or conference, often become enthusiastic proponents. But once they return to their newsrooms, just as often they become frustrated because management is skeptical of the approach.

To some, constructive journalism is simply another flavor of the month, a trendy form of journalism that’s buzzy now but which will fade away soon enough. Remember, the constructive approach is unknown in many parts of the world, and a lot of editors and managers don’t fully understand it. They perceive it as a drain on time and resources, two things often in short supply at media outlets. Or they consider constructive journalism akin to those “good news” stories that grace the back pages of the newspaper or the end of a broadcast—heart-warming and fuzzy. Nice to have but not real news, skeptical editors might say.

That means that journalists eager to try out this approach often have no support from above and go back to working in a traditional conflict-centered mode: reporting on problems to the exclusion of anything else.

But this pushback usually stems from unfamiliarity, a reaction to a mindset that seems to run contrary to what experienced reporters and editors learned at journalism school or during long careers. A constructive approach brings real benefits to audiences, as has been outlined in previous chapters, but it can also bring benefits to news outlets, many of whom are struggling. Studies have shown that constructive journalism can result in higher audience engagement, more trust and more loyalty, which can lead to better revenue streams.

That’s something that everyone in management can get behind.

In fact, given the multiple difficulties the media faces, a new mindset might be necessary for the industry’s long-term survival, according to Joseph Odindo, a lecturer and former editorial director of Kenya’s Nation Media Group. “We must be ready to abandon the traditional and venture into the unknown. Doing business as usual cannot save news publishing from the twin pressures of hostile governments and the digital revolution.”

Problems scream; solutions whisper. Many problem-oriented stories – plane crashes, police shootings, pandemics, even a water-main break – are front and center and demand coverage. Quotes for these stories are easy to get. Solutions-oriented stories, on the other hand, are rarely breaking news events. But managers and editors must ask themselves, is the screaming type of coverage working for us all that well?

Since research shows that constructive journalism can improve audience loyalty, it’s up to newsroom leaders to afford the time, space and resources to capitalize on it, if that’s a metric they care about. The trouble is that click numbers still dominate.

But many experts, such as An Nguyen, Bournemouth University’s associate professor of journalism who led the CoJo Against Covid project, say page views are not the key metric. Most of the people represented by page views are casual readers. That’s very different from the loyal reader who spends more time with the publication or program and might support an outlet by paying for premium content, getting a subscription or joining a membership program.

For editors interested in adding a constructive element to the news mix, the question is how to invest scarce resources in these stories. Ultimately, editors should ask themselves: What are the most relevant, most valuable stories we can bring to our audience? What stories are we doing just because we’ve always done them? What’s missing from the public conversation? And is the current conversation moving our community forward?

In practical terms, this may mean reconsidering coverage: Do we have to cover the school board meeting (again) – or is our reporter’s time better spent examining how schools are changing their approach to discipline? Or, do we need to cover the latest local shooting like we usually do? Or should we send a reporter to a nearby city that has a response to gun violence that seems to be working?

Adopting constructive journalism practices at your media outlet doesn’t mean transforming your newsroom or overturning all existing workflows. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Once management has decided to introduce a constructive approach, what are the first steps? How can the change be initiated and carried out? Instead of revolution, think evolution.

Adding to the existing editorial mix: Constructive journalism is an add-on to an organization’s existing journalistic practices and stories. It can be implemented slowly as a trial-run without drawing too many resources from other areas. How about one solution-focused story a month? An experiment promoting dialogue between opposing groups once a year? One way to dip your toe into the constructive pool is to make your social media feeds more constructive. Open the dialogue with your audiences, ask more questions, get more feedback and implement some of the good ideas you hear. You might be surprised.

Retraining not required: Constructive journalism is not a completely different way of reporting. There’s no need for big retraining programs or for reporters to throw out everything they’ve ever learned. Constructive journalism is about seeing the news through a new lens. How about a one-hour constructive journalism seminar for the newsroom staff? Gauge the reaction and follow up if it’s positive.

Baby steps: One strategy is to start small. Take baby steps instead of huge leaps. How about putting one reporter on the constructive beat one day a week? Then follow reactions (social media engagement, comments, etc.) and get analytics if you can. Look at both qualitative and quantitative data on the value of this new constructive approach. Based on those findings, develop a constructive coverage strategy.

Dedicated team, special sections or general constructive culture? There are different ways to start down a more constructive path. It all depends on the outlet’s staffing and resources as well as its appetite for change.

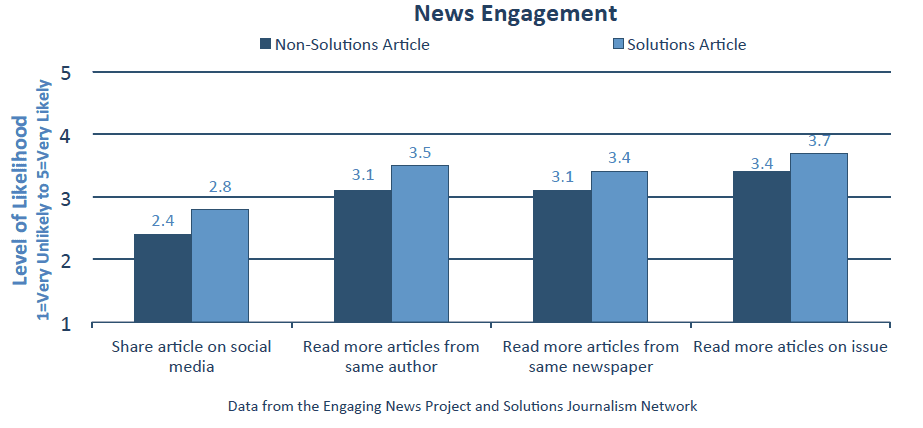

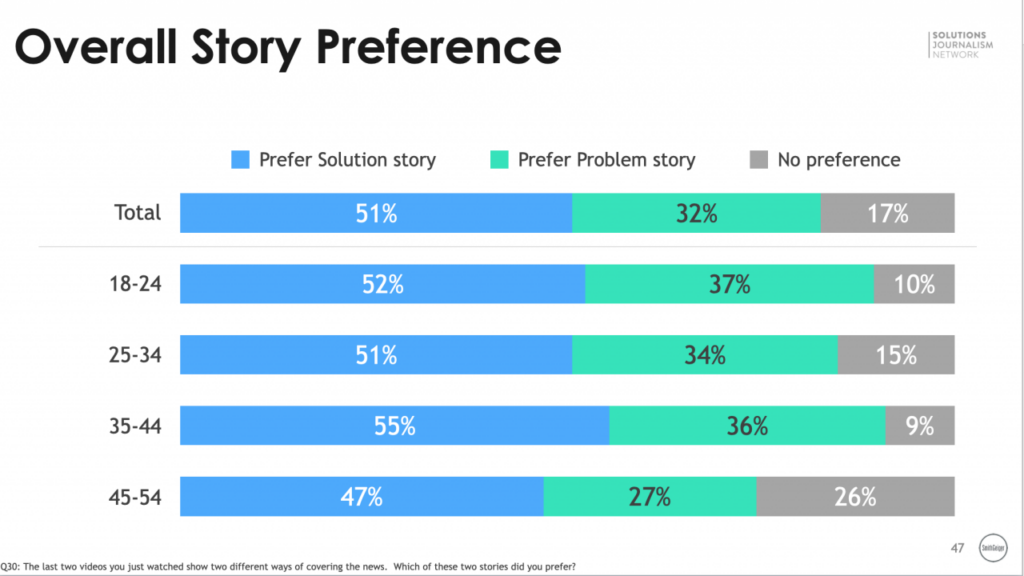

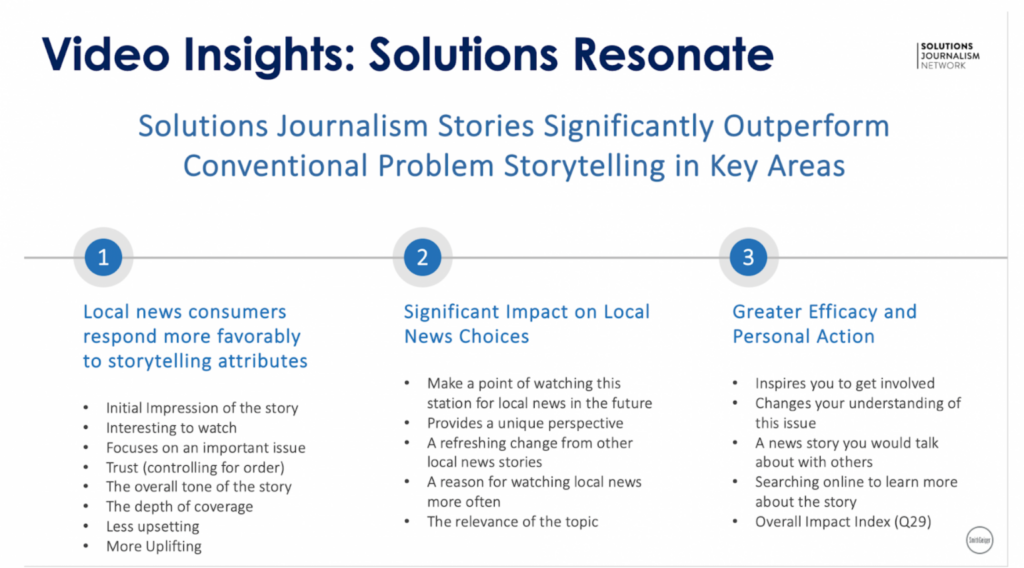

For skeptical editors and media managers, the data is starting to speak for itself. Several studies conducted over the last few years paint a positive picture of constructive journalism’s impact on audiences and news outlets. These studies were carried out in Europe and the United States, but the results are likely applicable to other regions as well. Below are a few findings:

Example 1: The Guardian’s The Upside section, which has a solutions focus, found that almost one in 10 readers on average shared these constructive stories on social media. (UK)

Example 2: News published in “Huffington Post’s” “What’s Working” section gets shared on average three times as often as the rest of the content on the site. (USA)

Example 3: A somewhat older study on viral news and emotion from the University of Pennsylvania looked at the entries on the New York Times’ “most emailed” list over three days and found that “positive” articles were consistently shared more often than “negative” ones. (USA)

Source: SmithGeiger/Solutions Journalism Network

Source: SmithGeiger/SJN

It is difficult to draw a direct line between revenue and constructive journalism — or any specific initiative. This is technically challenging and more long-term research is needed. But there are promising indicators that constructive approaches may lead to stronger revenue streams.

Example 1: “Die Zeit”, German weekly newspaper: “Die Zeit” editor-in-chief Giovanni di Lorenzo believes the editorial staff’s empathetic attitude towards readers is one of the factors for his newspaper’s increased sales, especially during the coronavirus crisis. After seeing reader numbers jump unexpectedly during the pandemic, the paper asked these new users why they had started reading the paper at that time. According to di Lorenzo, “one important answer was, ‘you neither played down the problem nor made it too alarmist’. From this I conclude that we found a tone that did not make one despondent even in difficult times.”

Example 2: “Sächsische Zeitung”, German daily newspaper: The “Sächsische Zeitung” has observed a similar trend. According to editor Oliver Reinhard, “new subscriptions are our golden tickets, and we have to say that there are clear indications that constructive articles lead to more subscriptions.

Example 1: Danish digital newspaper “Zetland” earns 90% of its revenue through memberships. The media outlet had 20,000 members in April 2022. A team of 40 employees, 50% of whom are journalists and editors, always try to prioritize their members’ needs, according to publisher Lea Korsgaard. That’s why they learn as much as they can about and from their community, using tools and formats that allow them to better listen to their members, such as open editorial meetings and surveys. This way they find out what stories to cover.

Example 2: Switzerland’s “Republik” is a digital magazine that has been publishing 1-3 stories per day since 2018. It was built upon an already existing community and had 28,834 members as of April 2022. The outlet has been profitable since 2020, according to co-founder Richard Hoechner. Their participatory revenue model combines subscription and membership models and multi-layer model:

Republik receives topic suggestions from readers, about 2-3 per day. Journalists who publish articles are expected to follow up on reactions and communicate with members/readers on the story topic. Transparency is prioritized and the magazine encourages lively discussions on topics or even taboo subjects with and among members. After a recent slight decline in member numbers, Republik started an ambassador campaign, attracting 5,000 “guests” on the recommendation of existing members. According to Hoechner, 10% of them stayed after a month of free use.

Example 3: “The Daily Maverick” in Cape Town, South Africa is not constructive, per se, but has a successful membership model. According to the paper, it uses readership growth and engagement as key drivers of revenue and investment growth. Its membership model is centered on content driven by investigative reporting, but the paper employs other models as well. A nonprofit vehicle funds its investigative unit and topics like climate change journalism through grants. Partnerships and impact investment funds provide resources for other content. Its approach to converting readers into revenue includes subscriptions and membership models. But its website doesn’t have a paywall which, according to CEO Styli Charalambous, helps the paper maintain its “duty to public service” by keeping content accessible to everyone.

Private donors, NGOs and other funders: Foundations and donors are often interested in supporting constructive journalism with its beneficial social impact. This was the biggest source of revenue for the Solutions Journalism Revenue Project. A large majority of the solutions journalism-related revenue generated by newsrooms taking part in the project and beyond came from a mix of community foundations and institutions regularly funding journalism as well as individual major donors.

![]() See handout 18: Grants, funding opportunities, awards

See handout 18: Grants, funding opportunities, awards

Example 1: The Kekere Storytellers Fund from Africa No Filter pays micro-grants to content creators, artists and journalists to create and publish unique, compelling content that shifts prevailing stereotypical narratives.

Example 2: The funders of the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel (USA) explicitly ask that reporting projects they support be solutions oriented.

Example 3: The Ford Foundation (USA), a large nonprofit with regional offices in Nairobi, Lagos and Johannesburg, gives sizable grants to projects related to investigative journalism, storytelling that gives voices to marginalized groups, and innovative projects that reach as many people as possible.

Advertising and sponsorship from local business: Specific news media are showing encouraging signs that advertisers want to be associated with constructive journalism and will pay for this opportunity. In this interview, John Montgomery, Executive Vice-President for Brand Safety at Group M (the world’s leading advertising agency) talks about the potential of constructive journalism for the advertising industry. Likewise local businesses tend to want to support reporting that elevates the positive aspects of responses to issues affecting their communities.

Example 1: German online news website “Focus Online” does not rely on a paywall, and constructive journalism seems to be attractive for monetization via digital ads. According to “Focus Online” Editor-in-Chief Florian Festl, “constructive surroundings are very popular and are booked by large customers, [many of whom] have a fundamentally optimistic and forward-looking philosophy. Clients can assume that crime, disasters and misfortunes will not be presented there as plain news. Every angle is framed around a solution and will have a positive vibe. Along with individual spots, all other forms of advertising have been proven to work better in these sections because they are perceived as having more value. The content rubs off on its surroundings.”>

Example 2: In 2020, “The Current”, a digit nonprofit publication in Lafayette, Louisiana, received $8,500 in sponsorships from local businesses to support its coverage of Louisiana’s developments in tele-health during the pandemic.

For a long time, a very competitive mindset prevailed in the media industry even though collaboration among media partners is not new. In the 1840s five media partners began working together to reduce the costs of relaying foreign news by telegraph, which is how the Associated Press (AP) was born. Since the mid-2000s, dwindling resources and declining audiences have sparked increasing interest in collaborations and partnerships. In 2018, the Center for Cooperative Media (USA) set up a database of more than 500 collaborative media projects around the world – and their list might be far from complete.

Global topics such as climate change and COVID-19 have increased cross-border media cooperation. International projects grew from 40 in 2017 to more than 300 in 2020. For constructive reporting, such projects and partnerships can be particularly interesting. When reporting on a concrete problem in one community, it can be highly instructive to compare a local response with the way communities in other cities, regions or countries are dealing with similar problems. Since economic links and interdependence have grown with globalization, it’s important to look at how successful responses can have negative ripple effects. In general, collaborative projects can greatly extend the impact and reach of solutions reporting.

Example: The Reentry Project was a year-long partnership among 15 local newsrooms in Philadelphia in 2016-18. Their members were trained by the Solutions Journalism Network and reported together on the challenges of prisoner reintegration and recidivism. Reporting spurred multiple policy changes locally and statewide in the state of Pennsylvania, and the group won the 2017 Associated Press Media Editors’ Community Engagement Award.

Two academic institutions analyzed the potential but also the risks of such partnerships.

Potentials

| Risks

|

In an evaluation of the Reentry Project, analysts discovered some tangible impacts:

Other impacts were less tangible:

Analytics, the analysis of data on the performance of online news content, has become a central part of many news organizations’ operations. In the print era, a media outlet’s success was measured by the sales of copies of its newspapers or magazines. In the digital era the success of each article, video or radio report is gauged individually. Therefore, unlike in the past when the journalist’s job was done when a piece was published, today’s reporters have a role in promoting their work to make sure it reaches the widest audience and to keep track of useful data to inform their journalism.

The performance of a journalist’s past stories could serve as good evidence of the quality of his or her work that can be shown to new editors who are approached. It could also build a case when applying for funding for journalism projects.

Why does analytics matter? This kind of analysis gives journalists and news outlets information about the audience’s preferences and engagement: what times do they consume news content the most? where do they do it? what kind of stories do they engage with? These insights are not possible without keeping track of the data, the metrics, and looking at developments and trends. It’s important to understand that metrics are not ends in themselves but rather a means to improve what journalists and news outlets do. It’s feedback.

That’s why it’s important to understand the meaning of the data gleaned from analytics tools. For example, if a story has a high viewership rate but a low dwell score, this may suggest that the content of the story was not as good as the headline and picture used to promote it. People clicked on it, but they didn’t stay long to read it.

If the case is reversed – a high dwell time but low viewership – this means that when people find the story, they usually read it or watch it but finding the story itself is not easy. This raises questions about whether the story is being distributed via the right social media channels or at the right time. All this data helps when deciding how, where and when to distribute your content.

It is important to not treat “negative” data – low viewership, poor engagement rates – as a failure but rather as important feedback that you can use to make changes. Any information that helps you understand your audience better should be treated as a win.

Chris Moran, head of editorial innovation at The Guardian, told the Reuters Institute: “Metrics are a vehicle for cultural change through which you can make journalists behave differently. I want the whole newsroom to believe that when we press publish, that is not the end of the process. And I also want the newsroom to believe that these numbers can help them improve their journalism.”

Analytics and constructive journalism: There is growing evidence that this form of journalism engages audiences and could help win over indifferent ones. (See section on impact.) Most of this research is from studies in the Global North and there is almost no data available about how well constructive stories do in other parts of the world such as Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Therefore, journalists from these regions should gather data about how well their constructive stories do and encourage their newsrooms to keep track of it. Thus, outlets can get a better sense of how well constructive stories are being received and how the organization should move forward with the approach.

Which metrics matter the most? There are plenty of metrics that can be tracked: click-through-rates, page views, engagement time, dwell time, etc. It’s not necessary to track all of them; the ones analyzed largely depend on the goals of the journalist or editor.

If the goal is increased engagement, measuring dwell time makes sense. If it’s audience growth, the number of new users or followers. Just observing the number of users without understanding what is driving them to your site is not very helpful. It’s important to track which stories users are visiting most often and spending time with.

Metrics are a tool that helps improve, not dictate, the kind of journalism that’s practiced. For example, it doesn’t make sense to significantly boost the number of short, funny videos on a site because the data shows high engagement with these. But metrics can help you see what kinds of topics appeal to your audience and the best time to post stories on which platforms. Metrics are best used to test hypotheses. If an outlet suspects their audience consumes news more in the morning, pieces can be published early in the day to see if they get more views. If it seems shorter headlines work better, the outlet could post a piece twice – once with a shorter headline and once with a longer one – and observe the response rates.

Impact beyond numbers: But numbers often can’t tell a journalist or news outlet everything about the kind of impact a story has had. This is important to remember since making a positive impact is one of the main goals of many journalists. Indeed, it’s why many of them got into the profession in the first place. Journalistic impact is defined as “change in the status quo at the level of an individual, network or an institution, resulting from journalism that gathers, assesses, creates and presents news and information.”

At an individual level, impact can come in the form of:

At a network level, impact can come in the form of:

At an institution level, impact can come in the form of:

So, while numbers are an important tool to analyze impact, quite often impact comes in forms beyond data. Journalists and news organizations should monitor anecdotal evidence and feedback – such as comments from users on the story or messages via social media. Sometimes they shine light on the kinds of personal impact that numbers alone can’t reveal.

For example, after the publication of a story about curly hair in Egypt, several parents got in touch with the author about how this story helped with the self-esteem of their own curly-headed girls. One message, from a single father, whose girl was teased at school because of her hair, was quite moving. He had no idea of the presence of such groups, since they were women-only platforms. After reading the article he got in touch with some groups to ask for tips about how to deal with his daughter’s hair and raise her self-esteem. That’s a form of impact that numbers cannot reveal.

![]()

How to integrate a solutions mindset in your newsroom

www.journalism.co.uk/integrate-solutions-mindset

The Keys to Powerful Solutions Journalism, 2019 Study

www.mediaengagement.org/research/powerful-solutions-journalism

Thinking “SoJo” in a newsroom (CFI)

www.conseilsdejournalistes.com/SoJo

Analytics/metrics:

Overcoming metrics anxiety: new guidelines for content data in newsrooms (.pdf)

www.reutersinstitute.politics/2021-final.pdf

Tool Review: Analytics platforms for newsrooms

www.medium.com/tool-review

Collaboration:

Strategies for Tracking Impact, A Toolkit for Collaborative Journalism (.pdf)

www.sjn-static.s3.amazonaws.com/Impact_Guide.pdf

“Collaboration is the future of Journalism”, Nieman Reports

www.niemanreports.org/collaboration-is-the-future-of-journalism

ProPublica Launches “Collaborate” Tool to Help Newsrooms Tackle Large Data Projects Together

www.propublica.org/propublica-launches-collaborate-tool

Case study in Collaborative local journalism

www.digitalnewsreport.org/case-studies-collaborative-local-journalism

Best Practices and Guides for collaborations

www.collaborativejournalism.org/guides

How networking will save investigative journalism

www.medium.com/how-networking-will-save-investigative-journalism