Home » Modules for decision-makers » Factory Floor » Promoting dialogue and engagement » Essentials

Main topics:

News outlet as facilitator, fostering dialogue with civil society, dialogue formats, dealing with divisive topics, collaborating with civil society, audience engagement, engagement on social media

Summary:

Constructive journalism seeks to open up new opportunities for dialogue on various levels – between the public and those in power, between journalists and their audiences, and among community members themselves. Especially useful is starting conversations between people or groups that are very divided. There are several initiatives that have tried or are trying to do this. More engagement in general with the public can also help bring people back to news outlets and raise trust. Collaboration is a part of this and can take many forms: journalists can ask their audiences what stories they should be covering or include them in the reporting process. Social media is a key platform for bringing constructive stories to your audience and a way to make the community members partners as well as news consumers. But it takes effort and monitoring to keep online conversations constructive.

Journalists who have built strong connections to their communities insist that engaging the public achieves something more fundamental than either promotion of their work or crowdsourcing, although these are certainly positive outcomes. A bigger benefit is making sure their work matters to their audience. For publishers and editors who oversee journalists’ work, engagement helps boost public support, something that news outlets need to survive.

Journalists who have built strong connections to their communities insist that engaging the public achieves something more fundamental than either promotion of their work or crowdsourcing, although these are certainly positive outcomes. A bigger benefit is making sure their work matters to their audience. For publishers and editors who oversee journalists’ work, engagement helps boost public support, something that news outlets need to survive.

Fostering dialogue with civil society is central to constructive journalism. This heightened engagement goes by different names, such as community-centered, engaged or “memberful” journalism. It is a strategy to remain relevant with audiences and to create a supportive community, important in these days of uncertain revenue models. Today’s relatively low-cost digital tools and techniques make this kind of communication easier than ever with various communities, be they based on a geographical region or a topic of interest.

How to start: There are several ways to engage more intensely with audiences, ask them questions, invite them to share their experiences, let them make suggestions or comments, get them involved in the research and even in the production of constructive stories. This can start with:

Reaching out to the public: Asking questions and surveying your audience can be a powerful tool which strengthens the connection between a news outlet and the public. This kind of request for input gives audiences a role and makes them feel a part of the reporting process. The German membership-based news start-up Krautreporter uses member input in a variety of ways:

These kinds of surveys can also be used to get buy-in for constructive journalism internally and help develop market strategies externally.

Co-authoring: In certain instances, a story could be co-authored by members of the community. It can provide a closer look at the reality of people directly dealing with an issue – a view from the front lines, so to speak. It can make a story extremely relevant. However, this kind of strategy requires a significant time investment. Note: this does not imply giving up editorial control, rather it’s an effort to give the audience a chance to contribute more (ideas, information etc.) to a story. The journalist should always have the last word before publication. Another co-authoring strategy is to ask the audience to go out themselves to record audio or video or write accounts related to an issue in their community. These personal “diaries” in video, audio or written form can be quite moving and give unique insights into lived experiences. Current technology makes recording easy for members of the public, although the editing process can be time intensive.

Crowd-newsroom: Correctiv, a German non-profit investigative newsroom, started some years ago to involve readers/users into the way it did journalism. The journalists built a special platform for this way of co-creating journalism, a crowd-newsroom. They ran a co-creation project over six months that included the following phases:

By one of the first investigations of this kind. It discovered that money laundering was behind around 10% of the real estate sales in the German city of Hamburg.

Many of the options for dialogue and engagement listed above are possible through social media, which is key in starting conversations, some of which might transition to the physical world. It’s important to put careful thought into any social media engagement strategy to ensure it is effective and relevant while remaining constructive.

Ideas for using social media for participation and engagement:

![]() See handout 16: Audience engagement during the entire story cycle

See handout 16: Audience engagement during the entire story cycle

Fostering dialogue with civil society is crucial in constructive journalism, one of whose central aims is to go to the heart of social and political divides and try to bridge them. While journalists have always gone to the places of friction in society, too often the result is people slugging it out on TV and online. They’re trying to score a “gotcha” moment that might burnish their reputation among those who feel as they do. While this might make for dramatic video or a post with a lot of shares, it usually doesn’t move forward the debate or solve an issue. People become defensive, battle lines are hardened, and the other side is demonized.

Another, more constructive approach is to try to build respectful, fact-based conversations between people about the issues that matter deeply to a society. Only by talking to others can people find common ground and start tackling problems successfully. Of course, everyone will never agree on everything; there will always be strong differences of opinion. But getting people talking about even their deeply held differences is better than not talking at all.

Pillar 3 of the constructive model focuses on starting a dialogue among leaders and decision-makers but also with and among people in the community (see Module 1, Chapter 2).

In this sense, constructive journalism shares similarities with civic journalism (or public journalism). Widely discussed in the 1990s, it uses a bottom-up approach and sees community members as potential participants in public affairs, rather than victims or observers to be written about. It seeks to engage people and improve the climate of public discussion. These conversations are the basis of coverage since it encourages the communities to engage with issues that impact them.

Media outlet as facilitator: Constructive journalism aims to alter the relationship between media outlets and news audiences. In addition to being disseminators of information and interpreters, outlets with a constructive approach become catalysts and facilitators of conversations. These conversations give room for people to express their feelings and opinions or ask questions to those in power or to those living next door.

In the traditional model, journalists ask for people’s stories, record their experiences and concerns, and then package and polish them to share with audiences. It’s often a one-way street without follow-up or asking what audiences themselves might need. This alternative model aims for a real conversation, uncovering what is meaningful to people. The result is a fuller picture told from many angles as well as a deeper relationship with the audience.

Managing a constructive dialogue: It’s important that media outlets keep these conversations on a constructive path. That means not simply trying to pit one party against each other to watch sparks fly, but to keep the atmosphere calm and the tone respectful despite differences of opinion. Journalists should carefully consider how they ask questions to get people to honestly participate instead of retreating to their defensive bunkers (see Module 2, Chapter 1). Media outlets can facilitate constructive conversations and debates by:

Some news outlets following a constructive approach are putting this strategy to work. A few examples:

Political debate without the toxicity: Norway’s national broadcaster NRK launched a political debate aimed at finding points of connection and agreement. In “Einig?”, or “Agreed?” in Norwegian, politicians were chosen to participate in the program who were willing to abandon political posturing for honest conversation. Personal attacks and talking points were frowned upon. The editorial team also offered advice on how to lead a constructive conversation. The program was recorded in a garage rather than a traditional election campaign studio to strip away the glamour and drama. According to the show’s editor, panelists who came on talk shows were often more civil and real with each other before or after the show when they were having a coffee. The goal was to recreate that type of atmosphere when the cameras were rolling.

Dialogue (and dining) across divides: Germany’s Die Zeit newspaper ran a series that included face-to-face discussions between people on opposite sides of a political issue. Germany Talks (Deutschland Spricht) matched people up who lived relatively close together but who held very different views on certain political and social issues, such as climate policy, vaccines and gender equality. According to Maria Exner, who helped develop the format, a project evaluation showed that even a two-hour conversation helped reduce prejudices between people of differing political persuasions. The political views of many participants also inched closer to each other in many cases. Such events can “encourage the center of society to remain open and willing to talk,” according to Peter Coleman, a professor of psychology at New York’s Columbia University. The idea has been expanded to a program called My Country Talks that has had participants from over 30 countries. The Guardian runs a similar series called Dining Across The Divide, where people with opposing views on some of the more divisive issues in the UK break bread together and talk.

Boosting democratic engagement:

In Australia before federal elections in 2013 and 2016, citizens were asked through social media, meetings, publications and broadcasts what issues they wanted candidates in their districts to address. Then candidates talked about these issues at public meetings reported on by the media. Organizers found that there were issues flying under the media radar which did not figure in the public debate. The goal was to improve civic engagement and alter how journalists reported politics. This model is based on the “Citizens Agenda” project from Jay Rosen of New York University in which members of the public are not merely consumers or recipients of news, but co-creators who deserve to have a say in what journalists cover.

Consideration of political, social factors: The ability of the above models to open a constructive dialog depend largely on local political, cultural and societal conditions. For example, the Norwegian program Einig? was effective due to that country’s strong democratic and egalitarian traditions. In other countries and different political environments, getting politicians to debate in such a manner might be impossible. In addition, some topics might be sensitive or simply taboo. Under authoritarian regimes, open communication can get people in trouble. The journalist attempting to create honest and open dialogue should carefully take the current political and social climate into consideration.

When it comes to highly controversial and divisive topics, constructive journalism offers other approaches that can help promote mutual understanding and respectful exchanges. This can be particularly helpful for moderators in live interview situations and round tables or town hall meetings.

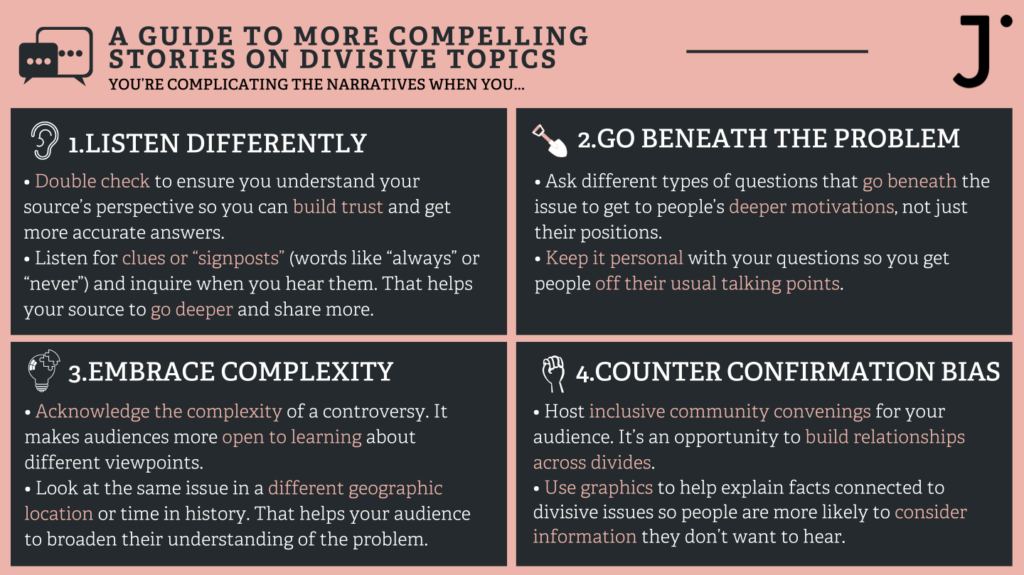

“Complicating the Narratives”: This approach by the Solutions Journalism Network and US journalist Amanda Ripley focuses on different ways to report on controversial issues that don’t inflame conflict and cause fear and division. Its goal is to help audiences make sense of what’s going on so they can consider how they want to move forward.

Ripley developed this approach after the election of Donald Trump in 2016. She wondered why she had not anticipated his victory and how she could have better understood voters’ motivations. She didn’t want to meet voters armed with her own prejudices and tried to question them in a different way. She understood that the essence of the conflicts undermining American society could not be reduced with conventional journalistic approaches. According to her, “when people encounter complexity, they become more curious and less closed off to new information.” She talked to specialists in conflict resolution: psychologists, lawyers, researchers, diplomats, mediators and rabbis – people who “know how to break toxic narratives and get people to reveal deeper truths.”

Ripley found that it’s useless to try to reason with an angry or frightened person. Irrational deadlocks can be real, and deep and seem insurmountable. For example, if someone feels threatened, it’s impossible to arouse their curiosity. They will remain enclosed in their “filter bubble” where they feel safe. Therefore, first, they need reassurance.

This reporting approach is based on four central ideas that help journalists:

Source: Solutions Journalism Network

![]() See handout 17: Questions to complicate the narrative

See handout 17: Questions to complicate the narrative

Conciliatory Journalism: A 2016-2018 Finnish research project brought together over 50 Finnish journalists, journalism students as well as researchers in the fields of journalism, communication and online interaction to look at an increasing level of polarized public discourse and the rise of disinformation. Conciliatory journalism was developed from the resulting findings. It takes a similar approach to Complicating the Narratives in that it seeks to support journalists writing about controversial and conflict-prone social issues. It values diversity, listening and social responsibility and features three core principles that are modeled on dispute mediation:

Dialogue Journalism – bridging divides: In the US, an organization called Spaceship Media has built an approach to reducing the animosity in public discourse that also subscribes to the idea of reporters as moderators and active participants in the news. This model also seeks to rebuild trust and burst information bubbles, but it also ultimately wants to attract and engage enough readers, viewers and subscribers to ensure the survival of a struggling news industry. The approach is built around gathering people on opposite side of contentious issues and starting honest dialogue by looking at four central questions:

Once they have answered these, identified a conflict and built a project around it, they expand the process into its seven-step “dialogue journalism” method that features moderated conversations and then telling stories in the media about them.

Evolution of attitudes: The above examples share many similarities and reflect a relatively new, emerging view of the journalist’s role. Twenty-five years ago, only a few in the media thought journalists should take on a more active role in societal conversations. But as polarization has increased and traditional news practices become less effective and sustainable, those ideas are changing. Research studies and anecdotal evidence indicate that where there is still reluctance among many in the industry to change the status quo, among younger reporters, there appears to be a desire to do things differently.

![]()

Elise Goldstein, Joseph Lichterman, How Correctiv invites readers into its investigations, The Membership Guide, 2020

www.membershipguide.org/how-correctiv-invited-its-readers-into-its-investigations

Amnesty International, Look beyond borders – 4 minutes experiment, 2016 campaign

www.youtube.com/4-min-experiment

Elizabeth Bader: The psychology of mediation (I + II): The IDR Cycle – A new model for Understanding Mediation, 2010

www.mediate.com/the-psychology-of-mediation

www.mediate.com/the-psychology-of-mediation-ii-the-idr-cycle-a-new-model-for-understanding-mediation

Elise Goldstein, Joseph Lichterman, How Correctiv invites readers into its investigations, The Membership Guide, 2020

www.membershipguide.org/how-correctiv-invited-its-readers-into-its-investigations

Andrea Wenzel, Daniela Gerson, Evelyn Moreno, Engaging Communities Through Solutions Journalism, Columbia Journalism Review, 2016

www.cjr.org/engaging_communities_through_solutions_journalism.php

Amanda Ripley, Complicating the narrative (video)

www.youtube.com/watch

SJN, Deep Listening and The BBC’s Crossing Divides

www.youtube.com/deeo-listening

The Citizens Agenda: An Alternative to the Status Quo of Elections Coverage

www.medium.com/the-citizens-agenda-an-alternative-to-the-status-quo-of-elections-coverage

Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds

www.newyorker.com/why-facts-dont-change-our-minds